How useful is a transformative gender justice for understanding gender-based violence among migrant women through the arts? Reflections from Efêmera and Ana by Gaël le Cornec – By Cathy McIlwaine

“It’s difficult to know what to say. I want to applaud the bravery, but that feels trite. This needs to be seen, to be heard, to be felt. Because, in a way, everyone needs to know this hurt, to feel this pain, until nobody does. I count my blessings that I have never suffered this much, and desperately hope for the day that no one will.”

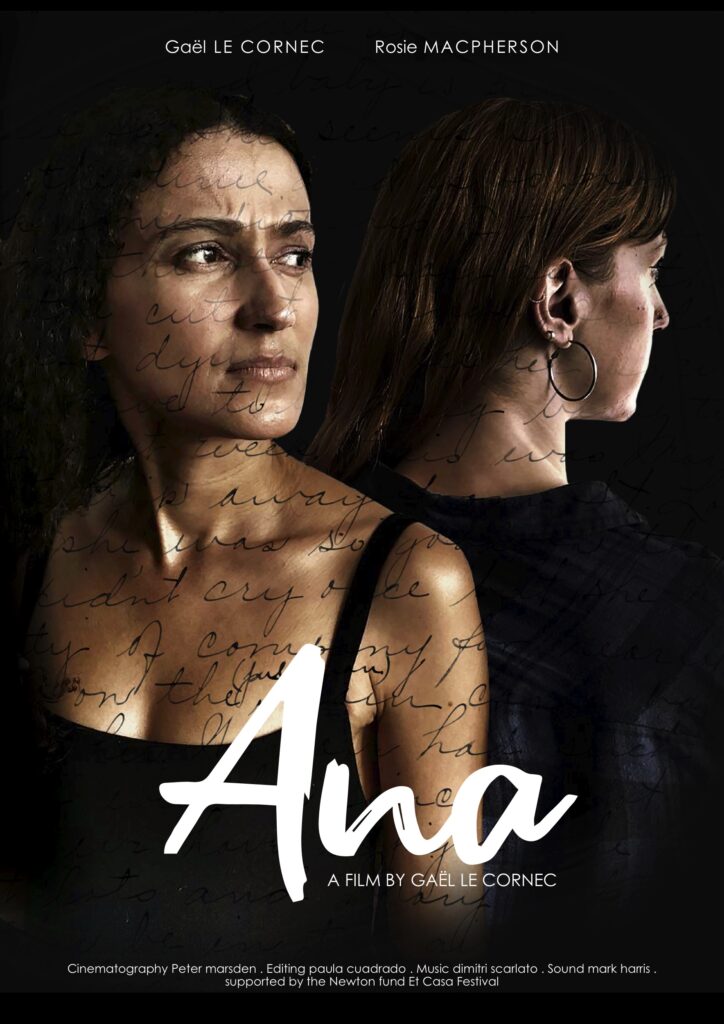

This is the response from a member of the audience member after the performance of Efêmera in Brighton in the United Kingdom in May 2018. Efêmera is a verbatim theatre play written and performed by Gaël le Cornec (with Rosie McPherson) as part of a collaboration with CASA, a Latin American theatre organisation, based on interviews conducted with Brazilian migrant women living in London who had experienced gender-based violence. Efêmera was produced a larger research project on Violence Against Women and Girls (VAWG) in London and in Rio de Janeiro in Brazil and subsequently made into a short film drama, Ana, named after the main protagonist (McIlwaine and Evans, 2018). The research in London was also conducted in close partnership with the Latin American Women’s Rights Service (LAWRS), a feminist and human rights organisation working with and led by Latin American women to address their needs through service provision and advocacy and with People’s Palace Projects, an arts organisation based in London working mainly but not exclusively in Brazil using participatory art as performance to address a range of social justice issues.

This blog reflects on the ways in which these artistic outputs can not only raise awareness of the issue of gender-based violence among migrant women, but also how these might be part of wider feminist transformative social change. Taking the lead from work on transformative gender justice that focuses primarily on gendered violence in conflict and transitional conflict situations (Boesten and Wilding, 2015), the discussion here suggests that it is useful to think of international migration as a transition over space which can create disruptions or healing in relation to gender-based violence and that such violence is an integral element of mobility processes. It also raises the issues of memory, commemoration and visibilising everyday experiences of gendered violence in ways that foreground women’s agency through adopting a spatio-temporal approach.

In relation to the experiences of Brazilian migrant women living in London, our research showed that 82 percent had experienced some form of gender-based violence over their life course, of which 30 percent occurred in the private sphere and 70 percent in public sphere. Gender-based violence was also endemic among women back home in Brazil where 77 percent reported experiences yet more than half suffered it again in London (52 percent). This reflects considerable transnational continuities in the incidence of gender-based violence despite important intersectional differences in the types experienced. Indeed, in the view of women themselves, similar numbers (44 percent) thought that gendered violence was the same or more widespread after they migrated as those who thought it was less likely to occur (43 percent). Yet, the core reasons as to why gender-based violence occurs is rooted in similar causes in Brazil and the UK: gendered power relations and inequalities and structural violence. These inequalities can often intensify in London as migrants negotiate the violence of a hostile immigration environment, language barriers, and institutional racism. This leads to violence against women and girls intensifying and/or being reconstituted in new ways in London in workplaces and in the private sphere.

Therefore, just as transformative justice approaches in post-conflict transitions need to recognise the structural gender inequalities that persist prior to war and which remain once the conflict has officially ended, examination of international migration and gender-based violence requires a similarly historicised but also spatial and life course perspective that acknowledges how gendered hierarchies continue to undergird violence in source and destination countries as well as transnationally.

While the social sciences can certainly provide the evidence based from which to explore these processes, the role of raising awareness as part of a wider effort to challenge hegemonic power can be usefully facilitated through performance art, theatre and film. Indeed, artistic production in general has been especially important among migrant and other excluded communities where conventional political expression and participation may be limited (Harman, 2019 on film; Pratt and Johnston, 2013 on theatre).

Returning to Efêmera, the play aims, and arguably was able, to communicate the importance of Violence Against Women and Girls in a visceral manner on stage in a way that the written word cannot. Efêmera tells the story of Ana (Gäel le Cornec), a Brazilian migrant who is interviewed by Jo (Rosie MacPherson), a British documentary film-maker. The interview takes a dark turn as Ana begins to open-up about her memories of childhood incestuous sexual abuse back home, her subsequent experiences of gender-based violence on arriving in London by a border guard at the airport and then at the hands of her violent husband. Ana’s story then re-awakens disturbing memories of gender-based violence from Jo’s past, binding the two women together as they recognise their shared abuse even if Ana’s entrapment through her insecure immigration status where she is afraid to seek help marks her situation as especially difficult. Ana and Jo’s memories travelled over space and time and the dialogue shifted between English and Portuguese. There is also an attempt to make several calls to action to the audience to raise awareness of gender-based violence, the need for safe reporting and the fact that all women who experience violence have a human right to protection from the state regardless of their immigration status. At one point, Jo responds to Ana’s claim that no-one would believe her if she reported the abuse she experienced because she was ‘illegal’, with ‘no human being is illegal, it’s just that you don’t have your papers yet’. This was a key element in the development of a transformative approach within the performance. It could be argued that Efêmera is part of a shift from testimonial to persuasive theatre where audiences are asked not just to be witnesses, but also to become activists as part of local and transnational feminist advocacy (Inchley, 2015).

Several of these issues emerged from the audience reactions to Efêmera in the Brighton performances in 2018. Some women both recollected and shared similar experiences in ways that they felt were cathartic:

‘Efemera was absolutely fantastic and emotional. It spoke to me on a personal and deep level. As a Mexican-American who has been sexually abused as a child and later on helped others deal with the same issues. It is inspired and I’m continually inspired by those who choose to speak out. Thank you!’

While this was from a migrant living in the UK, women with less in common with the character of Ana also related to the story:

‘I was incredibly moved by your show. Brave, fierce, important, shocking, moving. As a middle-class white English woman who has been sexually assaulted/raped even – the stories were close to my heart. That Brazilian woman are the subject of such terrible sexual, emotional and physical violence is deeply distressing … Thank you for your clarity your honesty and your courage.’

For those who watched the performances, some transformative processes were set in motion even if largely through catharsis rather than direct action as noted by this response:

‘As a child I witnessed a lot of abuse, as a daughter you try to forgive and forget. However, you realise that those memories have been affecting your private life consistently and quite strongly. It is our duty to expose, protect, heal and promote awareness. Thank you, Gael for doing your part.’

In light of the need to create a more lasting legacy of Efêmera, we turned to film as a way of ‘exposing’ and ‘promoting awareness’ in a more long-lasting manner. We did this through making a short video that showed some excerpts from the performance intermingled with the key findings from the research as well as portraying some of the main issues through animation and aimed at a policy-making audience.[i] We then made a short drama film based directly on Efêmera called Ana which aims to influence a more general audience through submission and screenings at film festival with plans to show it at workshops and seminars moving forward.[ii]

While this relates to the artistic work, it is important to remember that transformative gender justice approach is also linked with advocacy. Indeed, a related parallel project developed by LAWRS was their Step-Up Migrant Women campaign established in 2017 which is an alliance of 36 organisations from the women and migrant sectors in London working on Violence Against Women and Girls. The primary goal of the campaign is to ensure that the rights of survivors of gender-based violence take precedence over controlling immigration status so that women can report violence safely and secure assistance without fear. The aim is to develop a ‘firewall’ to separate reporting of crimes and the right to access support services regardless of immigration status. A central part of Step Up Migrant Women was to conduct research to provide the evidence base for policy-makers on the experiences of migrant women from 22 different countries (through a survey with 50 women together with in-depth interviews with 11 women and 10 representatives from service provider organisations as well as two focus groups – McIlwaine, Granada and Valenzuela-Oblitas, 2019). The campaign and the research have led to some significant successes including securing new guidance identifying the national position on information sharing with immigration enforcement authorities for victims of crime who are identified as being undocumented by the National Police Chief’s Council in December 2018, [iii] and a section dedicated to migrant women and a recommendation to government to establish a ‘firewall’ in the draft Domestic Abuse Bill published in June 2019.[iv]

Overall, and in thinking about how lessons can be learnt from existing research on transitional and transformative gender approaches that tend to focus on post-conflict situations, I have suggested that international migration is also an important transition across time and space in understanding gendered violence that occurred back home and that which continues in London. I have also argued that theatre, and to a lesser extent film, can an act as the fulcrum for remembering and recording memories of gender-based violence as part of a wider effort to raise awareness of the issue and engender transformative change. Yet this can be most effectively developed as part of feminist alliance-building at the community level through working with migrants from diverse origins. Individual experiences of gender-based violence have gradually become collective over time through art and through campaigns such as Step Up Migrant Women.

References

Boesten, J. and Wilding, P. (2015) Transformative gender justice: setting the agenda, Women’s Studies International Forum, 51: 15, 75-80.

Harman, S. (2019) Seeing Politics: Film, Visual Method, and International Relations, McGill-Queens University Press, Montreal.

Inchley, M. (2105) Theatre as advocacy: asking for It and the audibility of women in Nirbhaya, the Fearless One, Theatre Research International, 40: 3, 272–287.

McIlwaine, C. and Evans, Y. (2018) We Can’t Fight in the Dark: Violence against Women and Girls (VAWG) among Brazilians in London. King’s College London: London.

McIlwaine, C. Granada, L. and Valenzuela-Oblitas, I. (2019) The Right to be Believed: Migrant women facing Violence Against Women and Girls (VAWG) in the ‘hostile immigration environment’ in London, Latin American Women’s Rights Service: London.

Pratt G. and Johnston C. (2013) Staging testimony in Nanay, Geographical Review, 103, 288-303.

This blog is based on the following forthcoming chapter:

McIlwaine,

C. (accepted) Memories of Violence Against Women and Girls across borders: transformative gender

justice through the arts among

Brazilian women migrants in London. In J. Boesten and H. Scanlon (eds) Gender and Memorial Arts: From Commemoration to Mobilisation, Wisconsin University Press Critical

Human Rights Series: Madison.

[i] The video is available to view here: httpss://youtu.be/LPDNxtWB9e0 (accessed 1/9/19).

[ii] httpss://www.imdb.com/title/tt10503906/?ref_=nm_knf_t1 (accessed 1/9/19).

[iii] httpss://stepupmigrantwomen.org/2018/12/07/npccs-policy-we-need-still-need-an-end-to-data-sharing-practices/ (accessed 1/9/19).

[iv] httpss://www.parliament.uk/business/committees/committees-a-z/joint-select/draft-domestic-abuse-bill/news/chairs-statement-on-publication/ (accessed 1/9/19).