Collective knowledge: co-producing a research process in Maré, Rio de Janeiro

- By Moniza Rizzini Ansari, Julia Leal, Fernanda Vieira

It has been often said that co-production is key in international research collaborations, particularly when investigating the urban margins of the Global South, so as not to reproduce colonial and imperial dynamics of data extraction. Perhaps it has been less usual, however, to find insights on co-production from the point of view of field researchers “on the ground”.

As women working at Casa das Mulheres da Maré and providing support for other women facing multiple forms of gendered violence and hardships in the favelas of Maré, we offer in this blogpost our perspectives on an experience of co-production within the research project Resisting Violence, Creating Dignity. The research was developed by King’s College London in partnership with Redes da Maré, the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, People’s Palace Projects, Queen Mary University of London and the Museum of the Person, with the support of the British Academy.

The project creators partnered with key organisations and professionals who live and/or work in the favelas of Maré, not only acknowledging the accumulated knowledge that these actors have about Maré, but also valuing them as indispensable subjects of knowledge to “seat at the table”. In other words, in this research, it was sought not merely to talk about women in Maré, but with them. Both the (all women) participants and field researchers were seen as protagonists of the knowledge they shared.

This sort of “decolonial” stance on co-creation did not emerge in a ready-made manner, despite being an original aspiration of its creators. It resulted from a long process of exchanges and pacts within the transnational and cross-institutional partnership.

Social research in favelas has many complexities. While it potentially leads to social transformations, it also inevitably faces many contradictions and tensions. It is not unusual for this type of investigation to be based on hierarchised knowledge, with the residents of the favelas and peripheries often playing the role of informants or, at best, field researchers observing their peers, while universities take the lead of producing theory.

Added to this are complex interactions between universities and third sector organisations, as well as within Global North-South partnerships, which reflect unequal access to opportunities, possibilities and resources. In part, these complexities relate to risks of objectification or fetishization of favelas and poor communities. They also relate to a form of romanticisation or glorification of women who develop effective ways of cope and resist violence. Ultimately, they are permeated by hierarchical relations between local partners and Europe-based funds as well as a division of labour between those who go into the field and those who hold analytical power in the safe havens of academia.

Additionally, in a territory marked by police operations and armed conflicts in the context of the failed but persistent War on Drugs, conducting research in Maré in itself imposes several specific challenges – from talking about violence in a context where people deal with lethal violence on a daily basis, and are often silenced to adopting an ethical posture when listening to personal accounts of women who experience violence without considering their accounts only as research material.

One of the most important factors to highlight regarding the partnership between Redes da Maré and Kings College is that the former is an organization that has been operating for over twenty years in Maré, and that the field team works are frontline care workers. This makes it possible to offer responses to precarious situations and the research participants can count on assistance by the team after the end of the fieldwork.

Despite these considerations, we managed to experience a collective methodological process in the research Resisting Violence, Creating Dignity sharing equal responsibility, recognition and power (Bell & Pahl, 2018; Tinkler, 2012; Banks et al, 2012). We sought collective decision-making, consensus building, and acknowledgement of each partner as a co-author of the knowledge production process. Moreover, we adopted a feminist ethics of research, valuing collective processes, spaces of care and affects, from an intersectional and antiracist perspective (Tronto, 2011).

The field research started in the year 2020, and was organized between two teams. The Brazil-based team was formed by three workers at Casa das Mulheres da Maré, a space designed by Redes da Maré to foster the protagonism of women in the territory (two of which were born and raised in Maré). The UK-based team was made up of two Brazilians living in London at the time, and an Irish professor at Kings College London. There were also collaborators from UFRJ providing strategic advice to both teams.

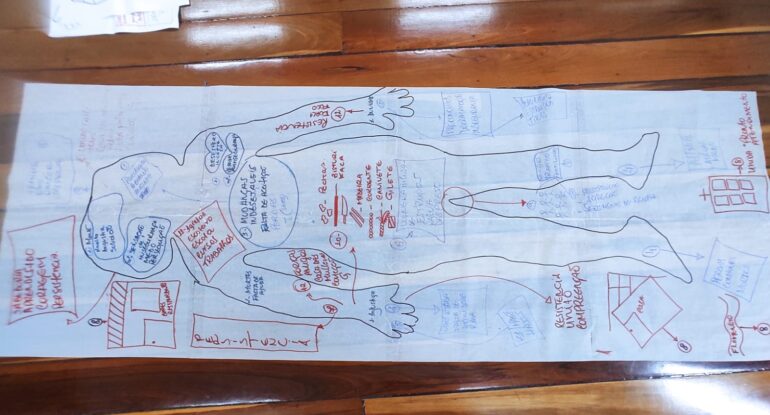

The field work of this 2 years long research project consisted of 4 phases: (1) in-depth interviews with 32 women from Maré; (2) focus groups with participants into groups of 5; (3) filmed biographic interviews with 10 artists from Maré, using the Museu da Pessoa’s methodology of Social Memory Technology; and (4) body mapping workshops with 10 women.

But the field research was not simply “outsourced” to the frontliners in Maré, keeping the foreign and academic institutions distant. During the process of the interviews, a space for collective reflection was established especially among what we can call the early-career researchers in both teams. On a weekly basis, we had online debrief meetings which were crucial in terms of supervision (as we listened to often difficult stories and there we could reflect on what affected us) as well as co-production (the elaboration of more sophisticated interpretations of the interviews, enabling us to collectively discover nuances and subtleties and re-establish field work strategies based on what worked and what did not).

Therefore, data collection and data analysis were simultaneous processes, led by the same researchers and enabling a creative process that is often not conceivable for field researchers on the ground, especially if they happen to also be care workers dealing with various cases at once in Maré. Gradually, the weekly debrief space that started without much planning, grew in importance and became a space of power, where decisions were taken and narratives about the research findings were produced.

But what made this a really powerful space from a methodological point of view is that it was from the creation of this routine of reflections that the production of collective knowledge could happen. All the debates, insights, and rifts were recorded and later served as the basis for a theoretical production at the end of the research. The main aspect to be highlighted here is the fusion of knowledges between the field team, composed of Maré residents and workers, and the UK team, which traditionally would be taking the lead of the theoretical production (and solely it).

This process of co-production resulted not only in the valorisation of the field team, but it also reflected in new research paths taken that actually make sense to the Maré women participating in the research. The relationship of the field team with Maré provided not only knowledge of the territory and the possibility of connections, but also affections and empathy that make the construction of academic knowledge more centred on the powers and agencies of the women participants.

It is important to highlight, in particular, the important role of the UK-based research coordinator had in respecting the autonomy of the team immersed in the field, strengthening narratives that emerged from the territory itself, and not a foreign perspective about Maré. The unreserved efforts by the London team, as well as the coordination of the research, ensured a co-production methodology that did not resolve, but certainly reduced traditional inequalities and injustices in academia.

One important result of this experience is how it reflected in unique engagements by the research participants. The individualized and group interaction among participants, built spaces of collective elaboration, with the methodological instruments of in-depth interviews and focus groups being spontaneously raised to a therapeutic dimension. Participants shared their testimonials, with trusted interviewers as well as among other participants, and often reflected on how empowering that experience was in producing feelings of complicity and trust and building affective networks of mutual support among women in Maré.

Many women, during and after the activities, expressed appreciation and a desire to repeat the meeting on a regular basis. As Casa das Mulheres was available to the participants in case they needed to return for any reason, such as for psychosocial and social-legal assistance, continuity was actually a possibility offered to them. Unlike many research projects where the researchers leave the field after collecting enough information, in this case, the team was permanently active in Maré. Therefore, the ethical commitments to these women went above and beyond the research process. Not always university ethics committee pay attention to the research aftermath, after they are gone.

Yet, it was not all easy. Before the research field had begun, the COVID-19 pandemic had erupted in Brazil and around the world. New transnational complexities emerged, especially considering that the Brazilian team was responsible for the fieldwork and, consequently, it was well defined who would be most at risk. At the time, Redes da Maré launched the campaign Maré Says No to Coronavirus, which involved territorial actions such as delivery of food baskets to families in situations of social vulnerability and, thus, the face-to-face work, along with health measures, was already part of the routine of the Brazilian team (see McIlwaine et al. 2023a).

Following the logic of co-production, the Brazil-based team had total autonomy to decide on the viability of the field work, with all biosecurity precautions – e.g., use of masks, spacing between people, activities with reduced number of people in open and ventilated rooms, use of alcohol gel, testing routine for the team, offered by Redes da Maré itself for free.

Another major challenge of the field research was the mobilization and preparation of the participants, which was predominantly done remotely due to the pandemic. In the mobilization process, we sought a diversity of women, in relation to gender identity, sexual orientation, age, race/colour, in order to try to reach the multiple ways of being women in Maré, as well as their multiple forms of resistance to violence. At the time, we asked them how they would feel more comfortable in participating in the research, whether they wished to try it remotely or in person. All of them replied that they wished to do the interview in person, mainly to ensure privacy and security.

Using the Casa das Mulheres da Maré as the place where the interviews were conducted was fundamental, not only because of the physical space itself, but mainly because it was a place designated for women, which made it a safe and welcoming environment for the participants and the team. It is particularly important to point to the autonomy and protagonism that the field team built together with the UK team, to these arrangements based on the expertise and legitimacy they undeniably carry, beyond what fund-holders might have preferred.

Again, we highlight the previous and continued work done by Redes da Maré and Casa das Mulheres da Maré, which strengthened relationships of trust between the team and the participants, and also ensured that during and after the research, attention and care to the participants were taken into account, with sensitive listening in a welcoming place. Today, as this article is being written, the three authors of this blogpost, who together formed the research field team, still work in the Casa das Mulheres da Maré and feel more equipped for their professional spaces, both due to new knowledge acquired in the process, and because they are still committed to improving the quality of life of the residents and workers of Maré, which we are (see McIlwaine, 2023b).

Recording these considerations in this blogpost is an attempt to contribute to methodological debates that seek to value local knowledge, but in no way seeks to serve as a model to the “right” ways of doing collaborative research. Still, we stress the importance of seeking partnerships between universities and organisations that develop territorial work in favelas and urban peripheries, especially community-based organisations. Partnerships with organisations that value and empower local knowledge, produced in peripheral territories, is essential for the construction of democratic and productive research environments. The search for such organisations, however, is only a first step towards genuinely collective productions, and is not, of course, the only possible means of achieving plurality of knowledge.

References

Bell, David M. & Pahl, Kate (2018) Co-production: towards a utopian approach, International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 21:1, 105-117.

Banks, Sarah et al (2014) Using Co-Inquiry to Study Co-Inquiry: Community-University Perspectives on Research, Journal of Community Engagement and Scholarship, 7: 1 , Article 5. Disponível em: https://digitalcommons.northgeorgia.edu/jces/vol7/iss1/5 Último acesso: 12/06/2023.

McIlwaine, C.; Krenzinger, M.; Rizzini Ansari, M.; Coelho Resende, N.; Gonçalves Leal, J.and Vieira, F.

(2023a) Building Emotional-Political Communities to Address Gendered Violence against Women and Girls during COVID-19 in the favelas of Maré, Rio de Janeiro, Social and Cultural Geography. 24: 3–4, 563–581. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2022.2065697

McIlwaine, C.; Rizzini Ansari, M., Gonçalves Leal, J., Vieira, F., and Sousa dos Santos, J (2023b)

Countermapping SDG 5 to address violence against women and girls in the favelas of Maré, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, Journal of Maps. https://doi.org/10.1080/17445647.2023.2178343

Tinkler, B. (2021) Reaching for a radical community-based research model. Journal of Community Engagement and Scholarship, 3(2), 5–19. Retrieved from http://jces.ua.edu/reaching-for-aradical-community-based-research-model. 2021.

Tronto, Joan C. (2011) A feminist democratic ethics of care and global care workers: citizenship and responsibility. Vancouver: UBC Press, 162–177.